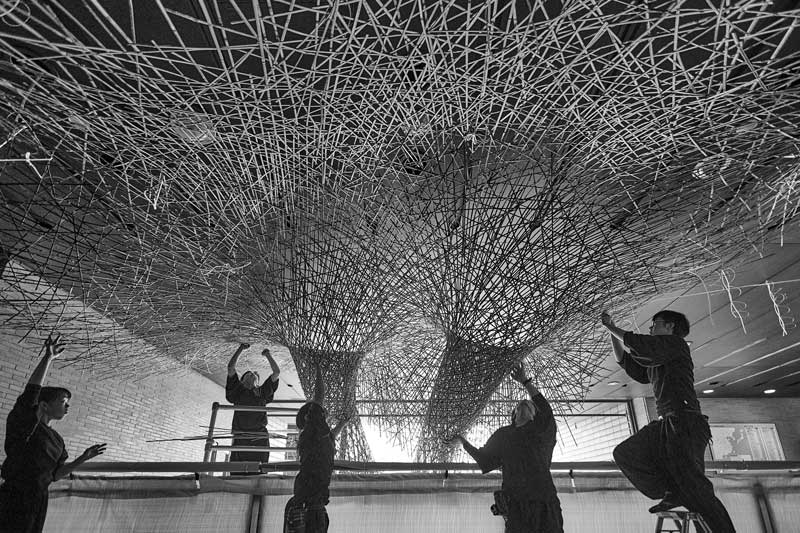

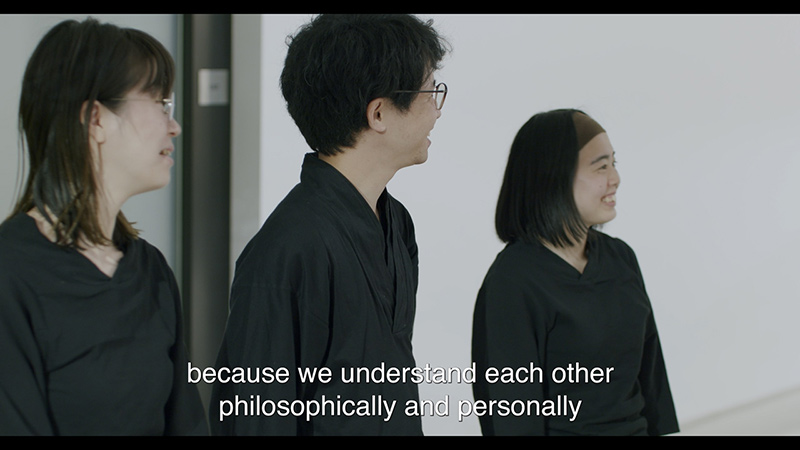

The world-renowned Tanabe Chikuunsai IV is a fourth-generation bamboo artisan who learned the intricate craft of weaving bamboo from his father and grandfather, and is now passing it on to his own children today. He is also training a team of valued and highly-committed apprentices. When his work was exhibited in “Life Cycles” exhibition at JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles in 2022, he constructed the gallery-size installation with the help of four of these apprentices, and in an interview (watch here), he explained the importance of Japan’s deshi or apprenticeship system. “Deshi means apprentice - not just an employee, but one who is also joining the daily life with a master,” Chikuunsai said. “Along with learning technique and tradition, we connect on a philosophical level.”

Photos by Minamoto Tadayuki

Long before there were schools, there was apprenticeship. Throughout the world, apprenticeship systems evolved over the millennia as the way that young people could learn creative skills from master artisans in their community, find a profession, help their masters in their studios, and carry traditions into the future. After the Industrial Revolution, however, such symbiotic relationships became increasingly rare in most parts of the world – except in Japan, where the apprentice, or deshi, is still highly valued. The deshi system is deeply rooted in Japanese culture and has been used to teach a variety of skills, from traditional crafts to martial arts. But the deshi system is more than just a way of passing down knowledge and skills from master to student. It is a way of life, a commitment to a particular path, and a relationship that can last a lifetime.

The deshi system can be traced back to ancient times, but it became highly formalized in the Edo period (1603–1868), with contracts and well-established curricula, particularly in disciplines like martial arts and the tea ceremony. Historically, the apprentice would begin young, perhaps as a teenager, and would go to live with a master artisan to engage in an important exchange: they would supply labor and receive the master’s training and knowledge. While apprentices sometimes came from the next generations of the same or extended family, the deshi system could also be a means of social mobility for young people from poorer families. For example, in the realm of tea ceremony, young people from a lower-class background could apprentice to a tea master and eventually become respected tea masters themselves. The term “deshi” thus came to denote not just a junior worker “learning” a given skill from experienced ones, but an intensive commitment to a master that formed a professional, familial and sometimes philosophical connection lasting for at least several years.

Tanabe Chikuunsai I (right), Tanabe Kōunsai (center) and Tanabe Chikuunsai II (left) at Tanabe Chikuunsai I’s Solo Exhibition at the Mitsukoshi Department Store, Osaka Newspaper unknown, July 1915 | Photo courtesy of Tanabe Chikuunsai IV

The deshi system continued to evolve throughout the Meiji period (1868-1912) when Japan opened up to the world, and traditionally hand-made and localized crafts such as ceramics and textiles faced competition from imported goods and new modes of mass manufacturing. Similarly in the decades after World War II, social and economic changes and the decline of heritage crafts led to a decline in apprenticeship; some masters were unable to find successors to carry on their traditions. However, in certain art forms like cuisine, garments, the performing arts, and some crafts, the deshi system has continued to thrive, with young people sometimes choosing an apprenticeship over attending university and others joining a master after graduation. While the length of an apprenticeship may vary, a decade is common.

For example, sushi chefs still famously rely on the deshi system to train their apprentices. The novice chef’s apprenticeship begins with basic tasks such as cleaning, washing dishes, and preparing ingredients. The apprentice then progresses to more advanced tasks such as making the perfect sushi rice and preparing sushi toppings, then eventually cutting fish. Throughout the apprenticeship, the apprentice is closely supervised by the master, who provides guidance and feedback on their technique, flavor, and presentation. The length of apprenticeship varies, but it can take up to ten years to become a master sushi chef.

Similarly, the making of an iconic silk kimono is a skill passed down through the deshi system and might take a decade. The apprentice first learns to sew and dye fabrics, and eventually work up to measuring and fitting customers, and may also spend countless years learning classic patterns and motifs before even considering innovating their own designs. The deshi system also still thrives in the performing arts like noh, kabuki, and bunraku as well, and the apprenticeship system has been integrated into institutions like the kabuki program of the National Theatre in Tokyo since the 1970s, as a way to pass on the high skill of brilliant performers to the next generation.

Recently, there has also been considerable interest by international artisans to train in Japanese crafts with respected experts. Though some traditionalists may not consider these foreign students “deshi,” some are hosted for programs that may take several years, for example with Japanese master chefs. There are also more casual programs for travelers who come to do an intensive months-long course in ikebana, carpentry, or other traditional Japanese arts.

As Tanabe Chikuunsai IV pointed out, the longevity of a family business is also part of the goal of the cycle of deshi. While the system has faced challenges in the modern era, the continued relevance of deshi is reflected in the number of long-term businesses known as shinise, often more than a century old and usually family-run. Japan has more of these businesses than any other country – at least 52,000 of which have been recorded – and these businesses have become a subject of fascination around the world as templates for long-term sustainable commerce that truly serves the community.

Photo #1: Provided by Kikkoman Corporation | Photo #2: Courtesy of Yamamotoyama | Photo #3: Provided by Domyo

In 2022, JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles hosted an event series spotlighting shinise and exploring their lessons for long-term business sustainability, with guest speakers from prominent companies like Kikkoman (food products), Yamamotoyama (tea and beverages), and Domyo (traditional craft). While some shinise have developed in surprising ways (like Nintendo, which originated as a playing card company in 1889), the vast majority are dedicated to traditional food and drink, crafts, and garments, the skills for which are passed down through the deshi system. In a time when sustainability, commerce, and even the very nature of meaningful “work” are the focus of intense debate worldwide, deshi serves as an inspirational mode of deep engagement with a craft and its past and future practitioners.