JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles is presenting the world debut of “BAKERU: Transforming Spirits” – an interactive exhibition inviting visitors to step into the supernatural world of Japanese folk traditions from Tohoku, the northern region of Japan, through the use of motion capture technology until October 20. BAKERU is a participatory exhibition where guests bakeru (transform) into projected characters wearing special masks and become a part of several festival scenes reimagined and created by WOW, a preeminent Japanese creative art and visual design studio.

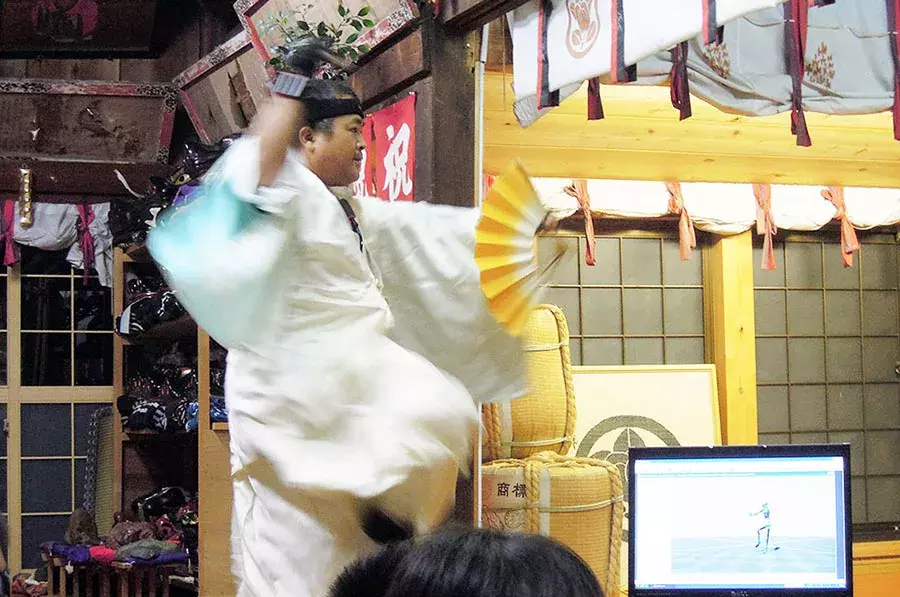

There is a Tohoku culture where people bakeru (transform) into divine beings including “Namahage,” “Shishiodori,” “Kasedori,” and “Saotome” by wearing masks and costumes to call on bountiful harvest and sound health. This tradition has been passed down from generation to generation in each locality, and there are countless folk traditions in Tohoku.

WOW interviewed Katsumi Sato, Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Education, Tohoku University, who studies Tohoku’s local performing arts by using modern day technology, to learn more about his research activities and the history and present trends in 2017 when the BAKERU exhibition was introduced in Japan.

You’re conducting a unique research by taking motion capture data of local performing arts and utilizing them in the educational scene. How did this come about?

Sato: At first, I wasn’t particularly interested in local performing arts but was intrigued in how it was taught. Unlike the general school system, there is no systematic way of teaching local performing arts. For example, if you were a ballet instructor, you would start by teaching the basic positions, but for local performing arts there is no step-by-step teaching method so you tell the students, “This is the easiest song, so just dance to it.” You would tell them to “learn by watching,” or understand things on their own terms. It seems that this is a unique Japanese teaching method which I was drawn to and I thought this (using motion capture data) could serve as another new education tool.

What are the technological differences between motion capture and video filming?

Sato: A video filming doesn’t capture content that all viewers want to see, and isn’t as useful as it seems. The videographer’s intentions are unavoidably present in the film, so the more highly skilled/professional the videographer is, the better and more appealing the film becomes. However, these films apparently miss capturing other moments. On the other hand, motion capture is more objective and can obtain data that can be interpreted freely.

Photos ©WOW

How long did you work on obtaining the motion capture data?

Sato: We filmed every few months, for about 2 years. Research participants observed the data and made changes to improve their dancing being captured. It seemed like seeing the discrepancy between what they thought they look like and what they actually look like made them wonder the “why’s” igniting ambition. But at times, there were major gaps between their own ideals and that of their instructors, so the changes they made to improve their data ended up being unacceptable. What’s unique about local performing arts is that you can try out new ideas along the way. You don’t ask questions but instead, you try things out and then ask your instructor, “what do/did you think?”.

What do practice sessions for folk performing arts look like?

Sato: There are no systematic practice methods. Usually, nobody plays the music for you, so you count the rhythm out by yourself, and practice an interval of 1 to 2 minutes over and over again. Unlike western music, there is no fixed musical pace. If you feel like practicing slowly, you would count the rhythm slowly, and likewise, the rhythm may get faster when you are feeling rushed. Metronomes are never used, so the rhythm of the actual performance can vary from slow to fast, just like in the practice sessions. The performers may pace up if they want to finish quickly, or because of the cold weather or rain. There isn’t a fixed rule in the structure of the musical piece either. If someone makes a mistake in a particular part, the custom is to repeat that same part again. For example, if a dancer drops a fan, the musicians will repeat the same part while the dancer picks up the fan. There’s much flexibility, and mess-ups are not particularly a failure. If the dancer dances well to the music, they might actually be forced to dance in loops forever.

Could you tell us more about the history of folk performing arts? I’ve heard they originated as sacred offerings to the gods, and they’ve transformed over time?

Sato: Many traditions of local performing arts in Tohoku are said to be passed down from mountain priests called yamabushi. In other words, performing arts were formerly preserved by such specialists. After the Meiji Restoration, the Ordinance Separating Shinto and Buddhism was introduced, and the way of yamabushi (Shugendo – a syncretic tradition of mountain asceticism-shamanism that incorporates Shinto and Buddhist beliefs) was abolished. As a result, the mountain priests had no choice but to become Shinto priests or farmers (commoners). As they became farmers, the performing arts that belonged to the specialists gradually turned into a ritual for the commoners. As these art forms seeped into the local communities, they eventually evolved into the many “local performing arts” that exist today. I believe it was after the Meiji Era that these art forms became truly “local.”

What are the origins of traditional masks and costumes, and how did they become “tradition”?

Sato: The costumes have changed with time. The reason why Saotome in the Taueodori dance is traditionally performed by young women may stem from the fact that female labor was needed in the rice fields. Saotome are women who serve the gods and there is an old saying, “the women need to plant rice, or else there will be no harvest.” The elaborate costumes that we see today were first introduced when the festivities started taking place around New Years’ day and the performers would appear at neighboring households or village-wide festivals. The costumes of Shishiodori (deer dance) are more subdued than those of the past. According to the successors, they were much more flamboyant long ago, but that became prohibited and evolved to the modest costumes you see today.

Many forms of local performing arts sharing the same name each carry a unique characteristic with different costumes and dance styles, depending on the locality. Are they derived from the same roots?

Sato: I think that’s a natural assumption. For example, Iwate Prefecture is known for Shishiodori but Sendai also carries the tradition. Some Shishiodori performers in Sendai claim that Sendai’s Shishiodori is older and spread to Iwate. In the past, if a lord approved a performing group, the group was given permission to wear the lord’s family crest. But in reality, there were so many groups that were approved and they all ended up carrying the same family crest.

In general, people tend to see traditional performing arts as something to protect, something unchanged, and something valuable that should be preserved. It is said that the widely known “Hayachine’s Take Kagura,” a yamabushi kagura dance, has kept the traditional form and culture. However, many performing arts have changed over time, and have lost the original meaning or form. Not much research has been done on these types of entertainment. Depending on sources, they are not even treated as “folk performing arts”. In truth, some of the arts have short history. We tend to think that things with a short history or that has changed over time has little value. But on the contrary, I think we can find new values in them.

WOW’S “BAKERU” exhibition offers an experiential installation in which the visitors can transform into something other than themselves by wearing masks, created based on particular folk performing arts. Is this concept of “transforming into gods by wearing masks” a shared concept in local performing arts?

Sato: Yes. Perhaps “transforming into something other than human” is the suitable expression. Many kagura dances begin with a dance that call the gods and ends as the performers take off the mask and put on another dance to part ways with the gods. In the past, strong emphasis was placed on having the audience understand the character roles allowing them to feel the presence of gods, rather than the performers transforming into gods themselves.

After the Great East Japan Earthquake, I happened to read an article on how the activities and roles of local performing arts have changed. Could you tell us more about that?

Sato: Week after week, many newspapers stated, “so and so local performing arts in the region have revived” immediately after the earthquake, but I’m not sure if that is still the case today. There were performing groups that I was in touch with that I couldn’t connect with over time. I think the earthquake raised a strong awareness for the local community, and folk performing arts have played a great role in promoting and sustaining that awareness. The decrease in updates could mean that folk performing arts have fulfilled their roles and that the revitalization efforts have been moving forward.

I think now is the time for localities to be established as communities. In that sense, we have to think carefully about the role local performing arts could play. I’m involved in the field of education so people may think, “just teach local performing arts in schools.” My concern is that having schools start delving into folk performing arts may lead for it to be forgotten and left behind. This is because if schools start incorporating this into their curriculum, the performers and the people around them will stop putting effort into preserving the culture as they will feel comforted knowing it is offered at school. Even if you’ve learned something in school, it doesn’t mean that you’ll continue when you are an adult. If no one continues the art form, it also means that the masters’ skills also become stagnant. The preservation of local performing arts is dependent upon having people who grew up with it to continue as adults. This is because when you look at local performing arts and festivals, you’ll notice that many children and people over 60 participate in them but the middle-aged group is small. When the current passionate masters are gone, the art itself might last in the school curriculum, but it could disappear in a flash. The other critical issue is that it’s mostly girls who are involved, and boys are severely lacking. I suppose girls tend to like dance and performing arts more than boys do.

It sounds like the generation that connects children and those in their 60s are crucial for the future of local performing arts.

Sato: The local performing arts and communities work hand-in-hand, so if one disappears the other will, too. Basically, if the local performing arts disappear, the glue holding the community together will be lost. Back in the day, people led similar lifestyles as farmers and probably had other things that connected them as a community. Today, communities are collapsing as such means holding them together are vanishing. In other words, if the local performing art flourishes, the community flourishes too. I’m hoping this opposite thought process might apply.

So, the implications of local performing arts are changing, and there are also problems of succession. How are you planning to use your research results and technologies going forward?

Sato: In the past, people took prayers for harvest very seriously, and local performing arts were sacred, with a strong religious aspect. But today’s local performing arts come with strong entertainment value, which needs an audience. The revitalizations of local municipalities start by proactively finding and securing various ways to share these performances. They could prosper as entertainment and could nurture a sense of pride in their local communities. Information Communication Technology (ICT) offers convenient communication and can be used to share about the greatness in local performing arts and to restore new meanings to the local region. I’m currently working on using ICT in such ways, and I’m excited about what it could achieve.

Professor Sato has kindly offered support for the exhibition.

Katsumi Sato, Ph. D. (Educational Informatics)

Born in 1972, in Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture, Sato is an Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Education, Tohoku University. With a research focus on “Information Communication Technology (ICT) in education,” he studies the effects of ICT in various educational scenes including but not limited to school education from the viewpoint of educational informatics. He has given learning support in projects that involve dance by using motion capture and CG animation technologies. The Great East Japan Earthquake was a pivotal point in his research career. Since then, based on his past research, he has been focusing on the roles of ICT in supporting local arts and in reviving local communities. He is keen on assisting the succession of local performing arts in a new way using ICT, especially VR.

ABOUT WOW

WOW is a creative studio innovating experiences in art and design. Based in Tokyo, Sendai, London and San Francisco, WOW is involved in a wide field of design work, including advertising and commercial works, installations for exhibition spaces, and user interface designs for prominent brands. The studio’s practice is based on a vision to bring positive change to society, and its original artwork and products have been exhibited both in Japan and internationally. WOW is passionate about exploring the tremendous possibilities of visual design; searching for solutions that are useful for society while revealing something true and profound.