Explore Nikko

Nikko, in modern Tochigi Prefecture, is about 87 miles north of Tokyo and for several centuries has been a popular destination for residents of the capital. It is the location of the Tōshōgū Shrine, the final resting place of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, which ruled Japan during the Edo period (also called the Tokugawa period). The shrine itself is significant for its ornate Ming Chinese-style architecture and its famous sculptures of the See, Hear and Speak-No-Evil Monkeys, it is the natural setting around the shrine that is truly breathtaking. Ieyasu's grandson, the Shogun Iemitsu, planted 200,000 cedar trees to line the approach to the mausoleum. The area also has many Buddhist temples, a famous lake and waterfall, and is particularly popular in the autumn, when the colors of the foliage are spectacular.

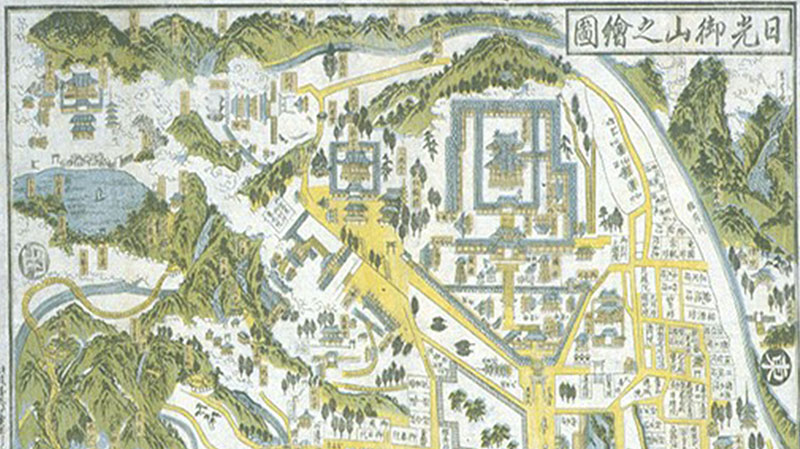

Map of the Mountains of Nikko, c. 1850

During the Edo period, though travel throughout the country was restricted by the government and often arduous, allowances were made for trips to important shrines and temples. One popular destination for residents of Edo (modern Tokyo) was Nikko, in modern Tochigi Prefecture, the location of the Tōshōgū Shrine. This shrine is the final resting place of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, which ruled Japan during the Edo period (also called the Tokugawa period). Beyond this important shrine and the monumental cedar trees that lead up to it, the area also has many Buddhist temples, a famous lake and waterfall, and spectacular autumn colors, all of which are featured in printed travel guidebooks and on maps like this example designed for mid-19th century pilgrims.

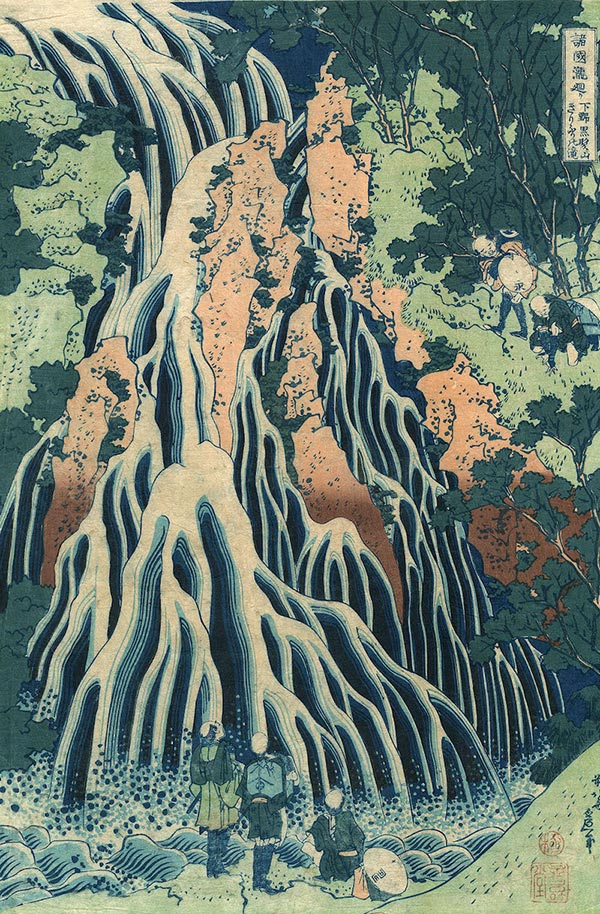

Kirifuri Waterfall at Kurokami Mountain near Nikko, Shimotsuku Province from the series A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces by Katsushika Hokusai, Meiji period reproduction, late 19c (Original c. 1831-1834)

Shortly after Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) created his best-selling series of horizontal prints featuring Mount Fuji, he designed a series of eight vertical prints called A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces (Shokoku Taki Meguri), depicting famous waterfalls located along pilgrimage routes. This series was ideal for showcasing the new, European synthetic pigment, Prussian blue, and it dominates the color scheme in each print. Most spectacular is this portrayal of the Kirifuri Falls near the Tōshōgū Shrine at Nikko. Here, a group of pilgrims look up in wonder as streams of water rush down the mountainside bursting with vitality and resembling the roots of a giant tree. Armed with his bold sense of design and this rich new pigment, Hokusai brilliantly captures the awe he and the characters in his print feel for the beauty and power of the natural world.

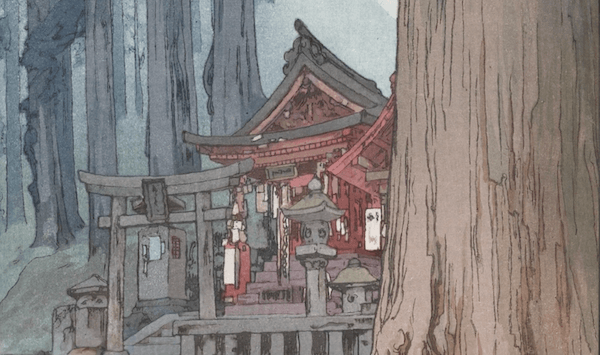

Misty Day in Nikko by Yoshida Hiroshi, 1937

About a century after Hokusai designed his prints of Mount Fuji and the Kirifuri Falls, Yoshida Hiroshi, one of Japan's most accomplished modern landscape artists, created this view of the cedar-lined approach to the Tōshōgū Shrine at Nikko. Although the shrine itself is significant for its ornate Ming Chinese-style architecture and its famous sculptures of the See, Hear and Speak-No-Evil Monkeys, it is the natural setting around the shrine that is truly breathtaking. Ieyasu's grandson, the Shogun Iemitsu, planted 200,000 cedar trees to line the approach to the mausoleum, lending majesty to the site. Yoshida, who was trained in Western style painting, designed woodblock prints that have the subtle color gradations and textures of watercolor paintings by layering as many as 40 colors in a single image.

Famous Sights of Nikko: Hannya and Hōtō Waterfalls by Yōshū Chikanobu, 1891

Yōshū Chikanobu designed woodblock prints during the Meiji period, a time when many aspects of Japanese society were rapidly Westernizing. Although he depicted many views of European-style buildings and customs in the newly renamed capital of Tokyo, his most lyrical prints are of more traditional Japanese scenes. Here, people dressed in traditional Japanese clothing enjoy the lakeside view and two of the waterfalls near Nikko amidst stunning autumn foliage. By the late 19th century, many new synthetic pigments were available to print designers, including vivid pinks and purples. Chikanobu uses these vibrant colors to depict people from the city relaxing and recharging their spirits with the beauty and energy of the surrounding natural landscape.

Nikko Outdoor Activity

Coexisting with Nature

© Yasufumi Nishi / © JNTO

Shinrin-Yoku | The Forest as Therapy

Today, people around the world are discovering the practice of Japanese shinrin-yoku. Translated as “forest bathing” (or most literally, “being in the atmosphere of the forest”), shinrin-yoku has deep roots in Japan’s Buddhist and Shinto traditions, but the term was only coined in 1982 by Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries. At the time, high-stress office culture and claustrophobic cities were starting to take their toll on citizens’ health, and the Ministry saw a chance to simultaneously help urbanites de-stress, and communicate the importance of forests in society by formalizing the concept of forest therapy. Thus, shinrin-yoku was born.

Explore Each Region

Return to Part 2

Nature: The Beauty of the Japanese Landscape

Main Exhibition & Virtual Tour

*Note: Japanese names in this exhibition are written in the traditional Japanese order, with the family name first and personal name last. However, if an artist has come to be known by a single name, (e.g., Hokusai and Kunisada) that name will be used for subsequent mentions.